This article recasts, in the first person, an interview originally published in Kozmojune, with each paragraph answering a question stated in its heading.

My art is rooted in a technique already known in ancient Rome called “graffito.” It is knowledge passed down from generation to generation in my family, once recorded in Murano’s Golden Book. For me it is not a simple inheritance: it is a foundation from which I can bring myself forth. Today I carry on this tradition, as an artist.

Epamphoterizein

Memory and art, for me, are two poles between which to oscillate. Without art history there would be no art; yet if I were to stop at memory and the “veneration” of great works, I would certainly not be considered an artist but a mere imitator. On the other hand, if I dispensed entirely with that knowledge, I would risk not being truly original. This weighty problem marks the very essence of art: does art compose its own history, or is it history that defines what art is? Within this whole, is there truly anything that can be called “non-art”? Something that lies at its margins not merely by subjective judgment? Does anything really escape a more or less shared subjective judgment?

I work with a particular technique—I apply gold leaf to glass and then incise it—and this particularity often risks having me perceived only as a craftsman, concealing the intellectual labor behind every creation. In this revived “humanist” struggle to avoid being trapped at either extreme, I chose to begin my exploration where the link resides between art history and the maker, between artist and artisan, between history and daily practice: to set the technical aspect free so as to reveal the purpose it contains—a personal artistic expression.

Imaginary Dialogue

If I could meet two ancestors in the studio, I would choose Francesco and Vittorio Toso Borella, father and son, like me and my father Marco. I would want to understand how they managed to work together while remaining independent artists; to know what they believed in, what their ambitions were, what they wanted from life. I imagine them answering with the wisdom I attribute to them: “We simply wanted to be ourselves. Be yourself too, respect yourself and have love for your family. Be worthy of what you’ve been given.”

Tradition

I am proud of my roots; perhaps that is also why I am so interested in history, tradition, and family. The Golden Book listed the families authorized to work glass: a kind of nobility of the trade. The Toso family was included there for the first time in the seventeenth century. What I do today—and I believe I am among the youngest to do it, and surely one of the last in the world—is possible only thanks to developments and decisions made by my forebears: processes that made Murano what it is, the island through which Venice became the heir of the Roman Empire in glass. Two forces are in dialogue: one comes from the past and the other, mine, tends toward the future. For this I feel gratitude and a duty to carry this legacy forward with all my strength, to be worthy of it. I know that to succeed I must believe in myself, as Venetians and my family once did: with courage, despite the fear of failing.

Venice, the Epistemic Impossible

Venice is, to me, a miracle. It should not exist and yet it does. It teaches us that everything is possible, against all odds. It was born as the ancient world was collapsing: the first Venetians were refugees fleeing barbarian invasions. With nowhere to go, they sought refuge in the lagoon and built a dream: a city on water, where no one had dared to build. They made the impossible possible and founded one of the longest-lived republics in history. There was never an internal revolt, not even during the French Revolution. They were proud of that, and with good reason. Atlantis became reality for over a millennium—independent despite emperors, kings, and popes at its gates: a model for the world, ultimately for the United States as well.

Water and Glass

Water carries Venice and glass reflects it. Water is to the Venetian environment what glass is to its architecture: it completes the city’s essence, amplifies its power, reveals the true scale of Venetian civilization. Like water, glass has an amorphous structure: it is not crystalline but malleable and adaptable. It serves every purpose and, at the same time, eludes human will: it must be respected and understood. Like water, glass is dangerous and also an opportunity. Like glass, Venice is fragile and elusive. Venice is reflected in glass, and glass is reflected in Venice.

The Venetian Soul

If I had to speak today of the soul of Venice, I would say it has little in common with the past; perhaps it no longer exists. One still recognizes it in traditional sayings: pragmatic, witty, wise. Mass tourism and depopulation, often described as problems attributable only to the elite, are for me the most visible sign of a wider and deeper difficulty: a collective inability to imagine a different future. In fact, if you believe you cannot create anything worthy of the past, at best you will try to preserve what exists—and precisely for that reason, you risk losing it. Then, when you realize that the world has turned without you, you react with arrogance, closure, even contempt toward those who come to see you and visit your city; slowly you turn into a reserve, a zoo, a “Disneyland,” because you have resigned yourself to the role of the loser. This, to me, is today the Venetian—and perhaps Italian—soul: the opposite of what Venice was. Once again the two poles return: the past and the fear of not being equal to it—this time on a social, perhaps political plane. This is not about “Make Venice Great Again,” nor about promoting a new nationalism—that would be anachronistic and foolish. It is about accepting the challenge to move forward, with awareness of the past but without being trapped by it. For me, too, it is a difficult path: it means wanting to preserve not only the stones but the values. To fight for them also through art. And by “values” I do not mean faith in St. Mark or the return of the Serenissima, but freedom, pragmatism, and the courage to face complexity. The challenge is imaginative. The challenge is, in a sense, artistic.

The Roots of the “Graffito”

I work with a technique whose roots sink into ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire, which found a special resonance in Venice thanks to its connection with Byzantium. I am proud of this heritage and, at times, fearful of it. On the one hand I feel the duty to continue the tradition; on the other I want to explore the possibilities it opens up. At times it is not easy to work here; but I experience it as an opportunity, a link to distant places and vanished cultures.

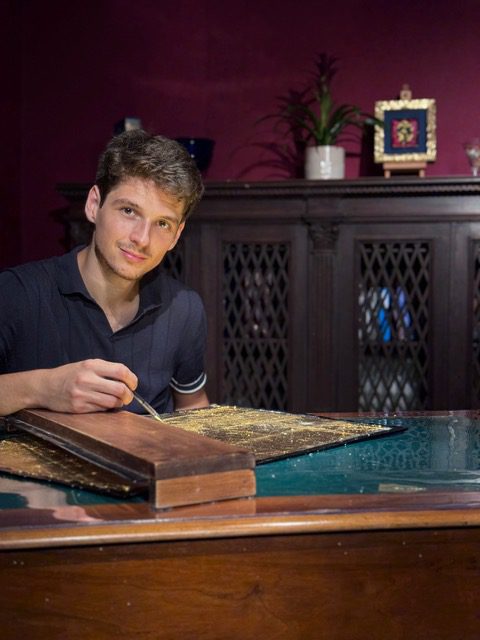

Materials, Process, Why I Love It

If I had to explain to someone who doesn’t know me what I do and why I love it, I would say that I work with precious materials and with an ancient technique that was at risk of disappearing. My father taught it to me—this is how it works here. The artifact is extremely durable; it lasts for centuries. It is Murano glass and 24-karat gold leaf, engraved by hand over weeks, sometimes months, fired in a special kiln for at least half a day, possibly decorated with enamels and fired again: practically indestructible. And that is only the material aspect. Behind each piece there is an intellectual exploration. Taken together, all this explains why I love my work.

The Ancient Gesture’s Right to Exist

What drives me to bring an ancient gesture into the present is the will to make it the means through which people can see something new. In these few words I sum up the works I have underway.

“To Venice”

If I had before me a blank parchment and a quill, I would write to Venice: “You saved me.”